As many of you may already know, I am an active investor. However I have often asked myself what I would do if I had to switch toward a more passive, low-fees index fund approach.

I hope these few elements will bring some food for thoughts and I am happy to discuss them if you find some flaws in the reasoning.

But first, some theoretical points.

Look for quality

I believe that the most important thing for the long-term equity investor is to look for quality companies. What do I mean by quality? I mean a business that can provide a high return on capital employed, superior to its cost of capital .

It makes sense at a personal level: if I borrow money at a 10% interest rate and i can get returns at a 20%, i am getting richer. Inversely, if I borrow at 10% to get returns of 5%, I am getting poorer.

This is the same mechanism at the business level: a company create value when it earns returns above its cost of capital, and destroys value when its returns are below its cost of capital.

How do you know the cost of capital of a business? When the capital is made only of debt, it is straightforward: that is the debt’s interest rate. But of course the capital is also made of investor’s equity, who expect an adequate return. This expected adequate return is a lot more difficult to measure, and even academicians disagree about how to measure it. But at the end it does not matter: in the same way that you don’t need to know the exact weight of a person to know that he is obese, for some businesses the returns on capital are so high that you know they are way above the cost of capital:

- Games Workshop earns a return on capital of 90%: for each dollar invested in the business, it will return $0.90. Surely this business is creating value.

- LiveChat Software earns a return on capital of 150%.

- MSCI and SPGI earn returns on capital way above 20%.

In each of these cases, the returns on capital are so high that we can be confident that they are way above their cost of capital: they are creating value.

Note that return on capital is really more important than the growth in Earnings Per Share (EPS). EPS growth does not tell you how much capital you needed to generate these earnings, and it is possible that the amount was so enormous that the capital would have been better used elsewhere. In a similar, diminishing outstanding shares with share buybacks (bought at fair value) will increase EPS, but not alter the value of the business. So in some cases EPS growth is good, but only if this is achieved with a high return on incremental capital.

And I am not inventing this. In its 1979 letter to shareholders, Buffett was already saying:

The primary test of managerial economic performance is the achievement of a high earnings rate on equity capital employed (without undue leverage, accounting gimmickry, etc.) and not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share. In our view, many businesses would be better understood by their shareholder owners, as well as the general public, if managements and financial analysts modified the primary emphasis they place upon earnings per share, and upon yearly changes in that figure.

When you put your capital in a bank account, you care about the interest rate it pays on this capital. Buying a share is buying a portion of the company’s capital, so why wouldn’t you care about the return you are earning on this share capital?

Now there is a second element to look for: our ideal business should have also room for growth at these attractive returns. If the business reinvest its high returns at the same rate of returns, you have a compounding machine . If the returns on the incremental capital are disappointing, the management team should have used these earnings elsewhere (see my other article on capital allocation).

Finally, ideally you would like to achieve those returns without too much leverage. If the business has to borrow a lot of money because the initial return on shareholder equity is not satisfying on an unlevered basis, it means that the business is not so great and could suffer badly if any unexpected accident occurs (i am looking at you, COVID).

In a nutshell, we are looking for:

- High return on capital

- Room for growth at attractive returns

- Reasonable or low financial leverage

Considerations about price

This is all good, you might say, but since those businesses are earning so high a return on capital, surely their price is a reflection of this and their shares are forbiddingly expensive? Well, historical experience shows that it is not necessarily the case. As long as you do not pay a ridiculously high multiple for the business and the company keeps earning high returns, you should be fine over the long term .

Charlie Munger was saying the same when he stated:

Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return that the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six percent on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you’re not going to make much different than a six percent return - even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen percent on capital over twenty or thirty years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.

This point is absolutely essential. If it is not clear for you, let’s look at the following example:

- Business A earns for 40 years 20% on its capital, and keep reinvesting its capital at these returns

- Business B earns a more modest 10% on its capital

- Investor A buys business A with an unlucky timing: he buys at a high-ish multiple (let’s say price to book value = 4 ) and sells 40 years later at a much lower multiple of 2

- Inversely, investor B has a much better timing: he buys business B at a low mutliple (P/B= 2 ) and sells 40 years later at P/B=4

Which investor would you prefer to be? We consider for simplification purposes that there is no dividend nor buybacks nor any raise of additional capital. Let’s also say that both businesses’ shares are trading at the beginning at a price of $100.

Well, the below table should prove Munger’s point:

| Year | Share Price, Company A | Share Price, Company B | Capital, Company A | Capital, Company B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 25 | 50 |

| 1 | 30.00 | 55.00 | ||

| 2 | 36.00 | 60.50 | ||

| 3 | 43.20 | 66.55 | ||

| 4 | 51.84 | 73.21 | ||

| 5 | 62.21 | 80.53 | ||

| 6 | 74.65 | 88.58 | ||

| 7 | 89.58 | 97.44 | ||

| 8 | 107.50 | 107.18 | ||

| 9 | 128.99 | 117.90 | ||

| 10 | 154.79 | 129.69 | ||

| 11 | 185.75 | 142.66 | ||

| 12 | 222.90 | 156.92 | ||

| 13 | 267.48 | 172.61 | ||

| 14 | 320.98 | 189.87 | ||

| 15 | 385.18 | 208.86 | ||

| 16 | 462.21 | 229.75 | ||

| 17 | 554.65 | 252.72 | ||

| 18 | 665.58 | 278.00 | ||

| 19 | 798.70 | 305.80 | ||

| 20 | 958.44 | 336.37 | ||

| 21 | 1,150.13 | 370.01 | ||

| 22 | 1,380.15 | 407.01 | ||

| 23 | 1,656.18 | 447.72 | ||

| 24 | 1,987.42 | 492.49 | ||

| 25 | 2,384.91 | 541.74 | ||

| 26 | 2,861.89 | 595.91 | ||

| 27 | 3,434.26 | 655.50 | ||

| 28 | 4,121.12 | 721.05 | ||

| 29 | 4,945.34 | 793.15 | ||

| 30 | 5,934.41 | 872.47 | ||

| 31 | 7,121.29 | 959.72 | ||

| 32 | 8,545.55 | 1,055.69 | ||

| 33 | 10,254.66 | 1,161.26 | ||

| 34 | 12,305.59 | 1,277.38 | ||

| 35 | 14,766.71 | 1,405.12 | ||

| 36 | 17,720.05 | 1,545.63 | ||

| 37 | 21,264.06 | 1,700.20 | ||

| 38 | 25,516.87 | 1,870.22 | ||

| 39 | 30,620.24 | 2,057.24 | ||

| 40 | 73,488.58 | 9,051.85 | 36,744.29 | 2,262.96 |

At the end, Investor A will get an annual growth rate of 17.9% with an unlucky timing, while investor B, with a superb timing, will only earn 11.9% per year. The conclusion should be clear: if you are a long-term investor, as long as you buy a good business at a multiple that is not too ridiculous, you will enjoy satisfying returns. And if you are not a long-term investor, I wonder what the hell you are doing investing in equities.

Application to indexing

Enough for the theory. How could we apply these points to passive, low-cost index funds or ETFs?

One thing that often stroke me in the past is that usually passive investors want to invest into possibly every company under the sun, by means of an index that is a broad as possible. For instance, the VT ETF follows the FTSE Global All Cap Index, which covers approximately 8’000 companies over the globe. Same thing with the MSCI World Index, which covers 1’603 companies in the developed countries. Both have been returning around 7% per annum over the long term.

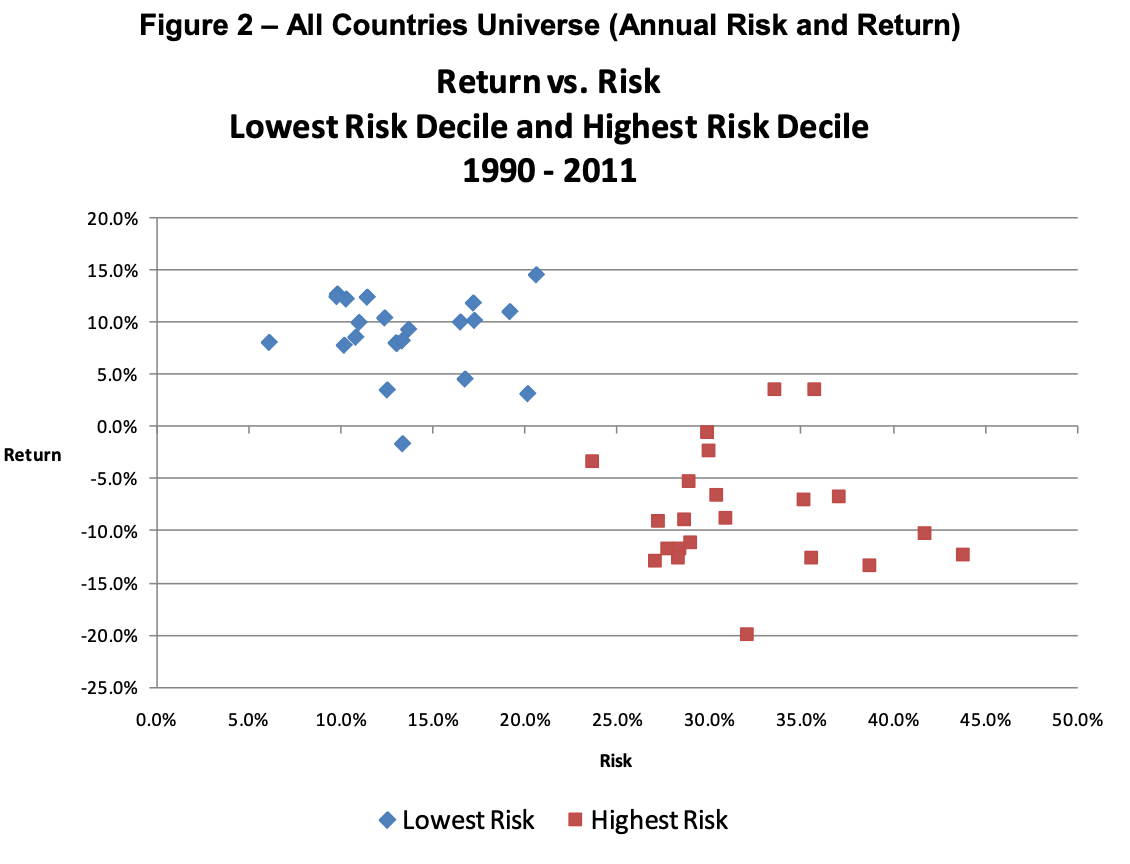

In my view, such an approach is guaranteed to cover a lot of good businesses, but will also invest in heaps and heaps of mediocre and degrading companies.

I get the point of diversification: we would like to spread our money over enough companies so that the failure of one particular firm is not threatening our portfolio. But if we invest in so many mediocre companies, is it not detrimental as well to our portfolio?

It is a bit like the wolf saying to the three little pigs: “Sure, you can have the brick house, but how about those two very nice straw and stick houses?”

I would like to improve this endeavor, not by adding as many stocks as possible, but by using the via negativa concept of Nassim Taleb: to improve something, ask not what to add, but what to withdraw.

What I would like to withdraw from these global indices is clear: the mountains of mediocre businesses that do not earn enough returns on the capital they employ. Couldn’t we find a new index such that:

- There are more than enough companies making the index so that we benefit from diversification.

- The companies making the index are all weighting on the quality side, which means:

- A high return on capital

- Some room for growth at attractive returns

- No excessive financial leverage

Well, it turns out that such an index exists: it is the MSCI World Quality Index.

This index is made of 297 constituents from 23 developed countries, which provides more than enough diversification for a passive investor. Furthermore, according to the prospectus, The index aims to capture the performance of quality growth stocks by identifying stocks with high quality scores based on three main fundamental variables: high return on equity (ROE), stable year-over-year earnings growth and low financial leverage.

Exactly what we are looking for! I would bet that such an index would provide a superior performance over the long term.

But theory is not worth much if it is not proven in practice. As Feynman used to say, It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.

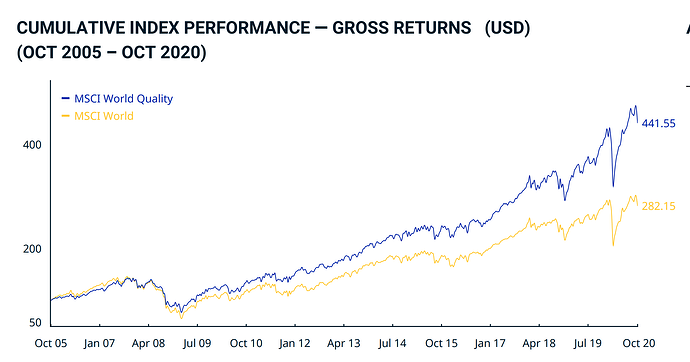

So how does it fare in practice? Very well, i have to say. MSCI provides data for the index since 1994 and since then (26 years, including two majors bear markets):

- The MSCI World Quality Index has compounded at 11.3% per annum

- The MSCI World Index has compounded at 7.53% per annum

The two indices have roughly the same dividend yields (1.73% for the MSCI World Quality Index and 2.06% for the MSCI World Index).

In other words, without counting dividends, $1’000 invested in 1994 in the MSCI World Quality Index would be worth $16’176 now, while $1’000 invested in the MSCI World Index would be worth only $6’603. This is not insignificant.

We should bear another point in mind: all of the companies making the MSCI World Quality Index are also included in the MSCI World Index. In other words, adding all the mediocre companies in the MSCI World Index creates a drag on performance of around -4%. Over the long-term, it makes a hell of a difference.

And this over-performance seems to be consistent. There might have been a few years where the MSCI World Index outperformed the MSCI World Quality Index (for instance 2016, 2012 and 2010). But there has never been a 10-years period where the MSCI World Quality Index has not beaten the MSCI World Index.

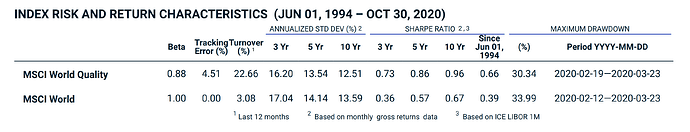

But wait a second! You might say, “Well, since this index provides consistently superior returns, then, according to the modern portfolio theory, an investor is bearing more risk while investing in it…”

I beg to differ. MSCI also provides its risk metrics for both indices, such as volatility, max drawdown, beta and Sharpe ratio, and all of them are in favour of the MSCI Quality Index. In other world, buying quality provides superior returns while bearing less risk than buying an all-world index. So much for the modern portfolio theory.

Conclusion

As I said at the beginning, I am not a passive investor as I like to hold good companies that will compound their capital at an attractive rate over the long term. But if I had to follow the passive, low-cost index funds route, I would surely invest in something akin to the MSCI World Quality Index. In the long term, quality always matter.