I like the (I think it was Morgan Housel’s or someone similar) quote/paraphrase:

“Doing the average thing for a very long time,

brings way above average returns”.

I haven’t seen hard facts but that’s only because I never looked, I believe this statement.

What’d be interesting to try to understand is what’s the thought process behind this. I know the obvious answer is greed when buying and fear when selling, so in a way driven by perceived momentum (“it’ll continue going up, I will make money, it’ll continue going down, I’ll protect what I can”), but it just reeks of FUD and lack of planning on both directions.

I think it’s driven by loss aversion

Human beings are more dramatically impacted by a loss versus a gain.

Thus a feeling of seeing your hard earned money evaporate makes people very worried. Then comes various attempt to avoid further loss, the FOMO when market goes up a lot and you didn’t get back in.

My guess would be that most people don’t pay that much attention to the market. The news they’ll see is when a fund/stock like ARKK/TSLA does +100% in a short time - to which they’d think “Wow, that’s amazing returns, I should buy that stock/fund!”

Regarding selling when stocks are low, the above could also apply (they’d see the news when we enter a correction/bear market) but I’d think it more likely for people to simply be unprepared. Mostly psychologically but potentially also financially. They buy stocks under the assumption - that they are sold - that they should expect amazing returns and then realize that they’ve lost a lot and can’t take more of it.

Some examples are how, on this board, we often see messages focusing on past performance when choosing a fund (US vs ex US vs momentum, vs whatever), or messages anchoring on the buying price stating “that investment is in the green. That investment is in the red, what do you think I should do with it?”

The Magellan Fund made 29% per year while Peter Lynch managed it (from 1977 to 1990). It was closed-end by then, so they knew the investors. Lynch said that most of their clients managed to lose money because they sold the fund low and bought high. That is just what retail investors do,

When building my mechanical strategies I focused on that problem by doing the exact contrary, buying more when the market is down and less when it is up (I am always invested at least 100%). However, as this is kind of martingale it needs a hard-stop.

My dad always says that when the Tagesschau runs a segment about the stock market crashing is the best time to buy.

Of course he ignores his own advice and buys obscure single stocks instead which he holds on to for way too long and sells them near bankruptcy ![]() (the stock’s, not his)

(the stock’s, not his)

One word (err 2 actually) - herd mentality.

(I’ve certainly been guilty of that too, many times, so call me sheep..)

Damn, I always thought it was the Blick article I have to wait for. I’ve been timing my transactions wrong! ![]()

Ah well, anyway, these days I just wait for @Cortana and @PhilMongoose 's posts.

4 posts were merged into an existing topic: Stock Market Participation rate

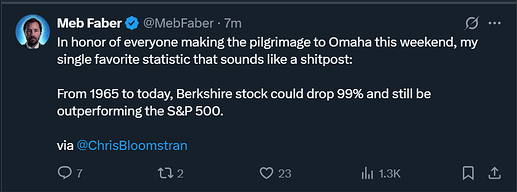

This blew me away and is a nice example of the long term effects of compounding:

(Source)

Also was a bit torn where to post this, given its mix of stock picking and long term effect of just outperforming an index of the ~500 largest US companies by … Goofy checks out the latest BRK shareholder letter … incredible 9.5% annualized!!!

Compounded Annual Gain – 1965-2024 … BRK: 19.9%, S&P 500: 10.4%

Overall Gain – 1964-2024 … BRK: 5,502,284%, S&P 500: 39,054%

Let that close to 10% additional gain work for six decades or so and you make about a hundred times more …

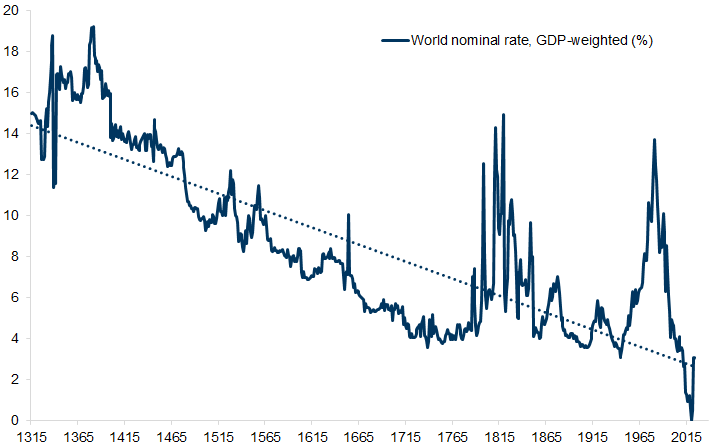

Nominal bond yields, GDP-weighted, 1315-2024

The very first drop seems to coincide with the end of the Hundred Years War ![]() .

.

This one is really quite something, IMO:

“Of all the progress of the past 10,000 years in raising human living standards, half has occurred since 1990.”

(Source)

Original Economist article (paywalled): How golden ages really start—and end

Pretty sure fire, the wheel, agriculture and the progress of medicine from the onset of Humanity to 1990 account for more than half of the living standard people enjoy today. Also, tap water, electricity, cars, planes,…

Computers account for a lot, but really not as much. Smartphones and half of the “progress” we’ve made since then doesn’t even scratch 1%, if the number attached to them is even positive.

Edit: of course, spreading it inside the world may have accelerated since 1990. Since there’s also been a population growth, it’d be interesting to know if we’re talking standard of living pondered by the slice of the population it applies to or total nominal human beings affected.

I think it refers to raising standards across the world.

Largely this is bringing large parts of China out of abject poverty.

Such a sobering reality of real world

Yeah… then again many countries there with phenomenal quality of life.

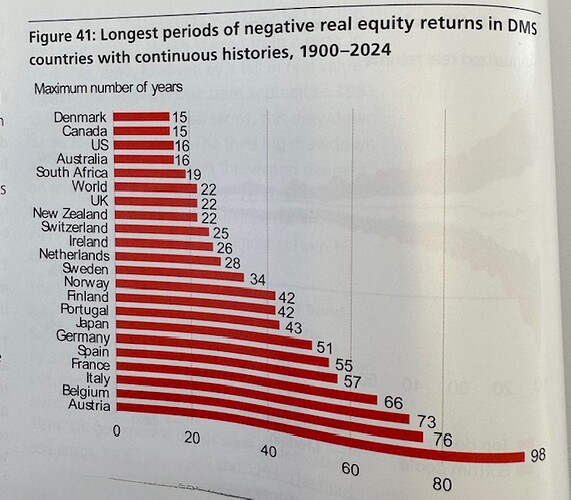

In the real world you do dca and are diversified however.

So one small country going close to zero and therefore making the longterm gains really bad, will not affect a globally diversified investors much.

These stats are extremely startdate sensitive.

Austria did not have terrible gains the last decades for example.

I think global diversification is not a norm. Many investors have huge home bias (even more than optimal)

So there can be situations when someone gets stuck in this as soon as they retire

Except for those hardcore lumpsum advocates (even in this very forum).

Note the “world” – whatever that means – line: 22 effing years.

“VT and chill” becomes "VT and literally chill for 22 years? ![]()

![]()