Hi folks!

Some of you have seen that I’ve opened accounts with frankly. to give in to an experiment I’ve been wanting to try for some time: timing the market using moving averages. I’ve now launched it and will provide regular updates as to how it is going but for now, let’s spend a few posts talking about the setting.

So…

.

What are moving averages?

There are several kinds of moving averages. For the purposes of this experiment, we’ll only focus on Simple Moving Averages (because I’ve not studied the use of other kinds well enough and the few dabbling I’ve done with them is not conclusive to how I want to use them).

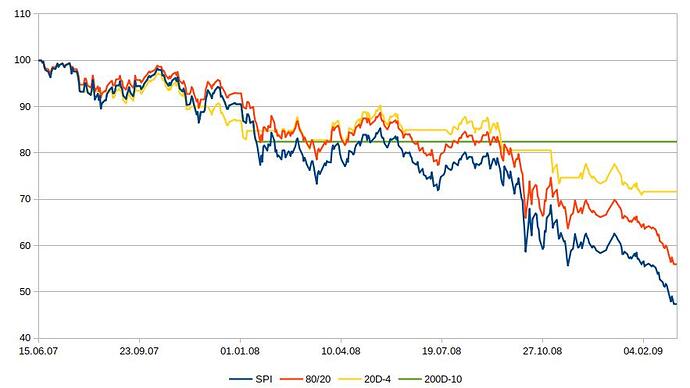

They are averages drawn on a set period of time, that then move with the current date. When the curve you’re studying goes up, moving averages are usually below it (because past data was lower than the more recent one). When the curve you’re studying goes down, moving averages are usually above it, given it either goes low enough or for a long enough period of time.

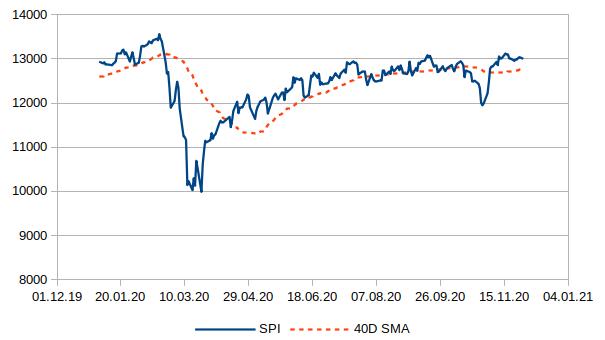

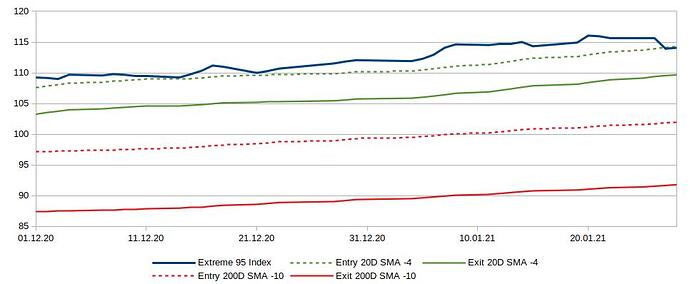

The graph below shows a plot of the SPI (blue line) and its 40 days Simple Moving Average (dashed red line) from January to November 2020:

.

How can they be used to time the market?

The magic can occur because moving averages don’t behave like the curve you’re applying them to but they cross it, both when it goes down and when it goes up. And they cross each other, providing easy to identify data points that can be put to use… or not.

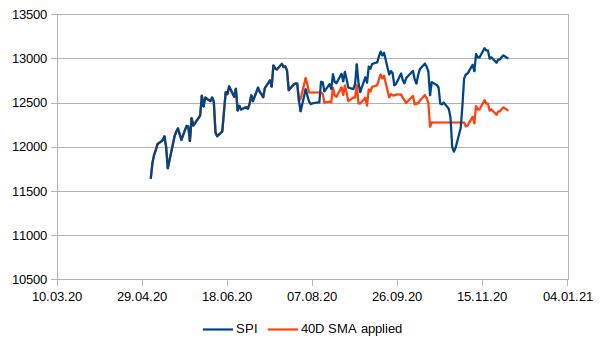

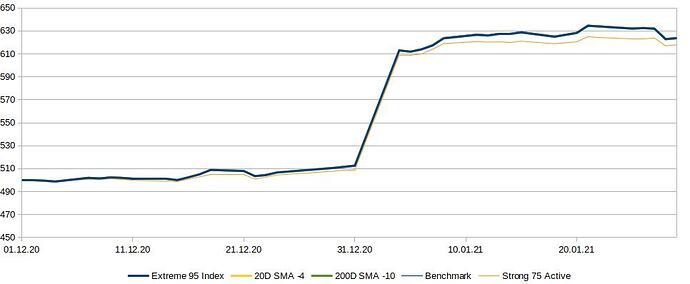

See that graph below? The red line is what would theoretically have happened with an investment “tracking” the SPI (blue line) from January to April this year, if it had exited and entered the market based on the crossing of the 40 days Simple Moving Average, checking at close what move should be made and buying/selling when the market opens.

.

Notable is that an investor following that strategy would have avoided most of the drop and increased their returns.

But… see that other graph? That’s what would have happened with the same strategy, this time from May to November 2020:

.

Moving averages are not magic but they can help inform decisions. They are very good when the market goes up unequivocally, and then goes down significantly, then starts going up again, but slowly. They are awful when the market is basically flat but volatile: they start providing entry and exit points all the time, you keep getting in and out at the wrong time and you incur fees. That’s bad and can drain your account while everybody else is staying flat.

The previous graphs incurred no fees when buying or selling assets, the fund was following its benchmark index without discrepancy and had a TER of 0%. The investor was paying no taxes. You can imagine the effects of flat markets on your investments when you are subject to spreads and fees: the wrong strategy can quickly melt your assets when everybody else is standing still.

.

What can I expect?

I can expect downturn protection. Sharp downturn? Protected. Watch them panic about their portfolio loosing value and/or hesitating about the right time to enter the market again and grin.

I can expect false positives. No matter how you design your strategy, there are some points right after you’ve made a move where you are vulnerable. If the market changes behavior just after that, you’ll probably face a false positive. That means that you are selling low and buying high. You are loosing returns. That is fully normal, it happens from time to time, or often, depending on your strategy. I’ve put a real empasis about what kind of false positives I was willing to accept while crafting my strategy.

The protfolio can go down to 0 in a slowly decreasing market. Downturn coverage isn’t 100%.

The portfolio can go down to 0 in flat but volatile markets. Some strategies can reduce that, I’ve designed mines to lower that vulnerability.

I may get better returns than the fund I’m using at times. Overall returns are deeply affected by the starting point and behavior of the market, so I may beat the market, or not.

I can expect lower volatility than a (near) 100% stocks fund.