These are all assumptions, but:

Most likely scenario: the problem in these cases would be the leadership. Apple’s brand, intellectual property, factories and network would still be worth something. Someone is likely to step in and acquire them (albeit at a lower price than their previous valuation) or initiate a merger. In this case, previous shareholders are likely to get something back (while not necessarily being made whole, which is ok because they are the ones with the deciding power who led the company in that direction, CEO notwithstanding). Everything remains orderly, the index may tank a bit (or more than a bit) but would be likely to rebounce: Apple’s business didn’t disappear, it is simply now done by someone else, who is also listed in the index.

Less likely but can happen: nobody steps in and the company goes bankrupt. In that situation, shareholders come last in line to get anything back from it. Let’s assume they get nothing, the stock is delisted, its shares are worth $0. This is likely to create contagion: investors become more hesitant to put their money in similar companies, money goes out of the stock market (and so, out of VT, VT tanks). It doesn’t cease to exist, though (it goes to bonds, bank accounts, real estate, gold, crypto, quality wine bottles or whatever).

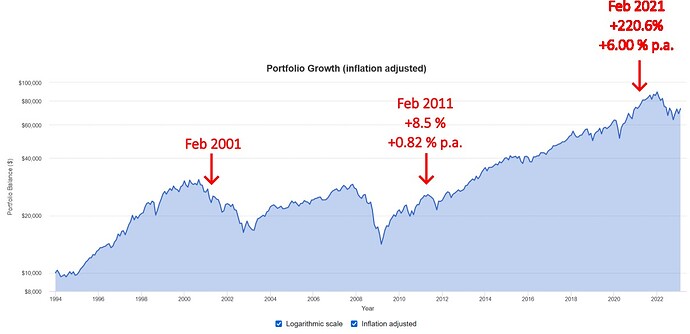

On the longer term, the shock would pass, investors would see that companies are still valuable and still produce cashflows (that yogurt you’re buying at Migros? Nestlé is listed too, the net profits they make on it are actually the shareholders’ profits) and as long as those net profits are not zero (the global economy produces value), they have value to some investors. The price of stocks (shares of companies) varies depending on how much investors are willing to pay for their profits. On the longer run, the economy keeps running, the profits Apple was doing are made by other companies (that are likely to be in VT), those who bought shares of those companies when they were suffering from investors’ timidity make out like bandits (VT holders who hold on to their shares through the turmoil capture the full market returns, those 7% per annum everybody keeps referencing -though it’s closer to 5% for the global world market-), those who come and buy later have a less lucrative deal.

Edit: of course, there is also the scenario where the change of leadership goes smoothly. Steve Jobs left for Tim Cook and Apple is still among the best of them.