That’s why I am happy with the market returns ![]()

Could you elaborate a bit on this interest rate risk or provide a numerical example?

How I tried to put it all in place in my head: so the interest rate sets the risk-free rate of return. If this rate is low, then a quality company A, being able to deliver high return, will be valued high. If the rate goes up, the return of company A is suddenly not so attractive anymore. What I don’t grasp is how the interest rate change influences inflation, company A return, and a non-quality company B.

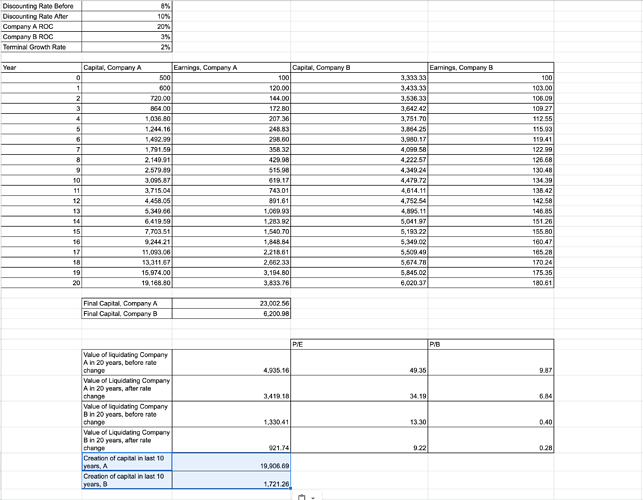

Consider the following simplified example.

You are the owner of two companies, Company A and B. Both are currently earnings 100 CHF per share in current year.

But A has a great return on capital (20%), while B as a poor one (3%). As a result, Company A has currently less capital (500 CHF) than company B (3333 CHF).

Let’s say for this example’s purpose that both companies will reinvest their earnings for 20 years and that after 20 years you liquidate both businesses. For simplicity we will assume that after 20 years you can get back all the capital of the company.

What is the current value of both businesses in this scenario if we use a 8% discounting rate?

What happens if suddenly the discounting rate goes up to 10%?

First, after 20 years, Company A will have a capital of 23’002 CHF that can be liquidated, while Company B will only have 6’020 CHF.

If you discount it at 8%, this gives:

- current value of 4’935 CHF for company A, or a P/E of 49.35 and a P/B of 9.87

- current value of 1’330 CHF for company B, or a P/E of 13 and a P/B of 0.4

If suddenly the discounting rate goes to 10%, then:

- current value of 3’419 CHF for company A, or a P/E of 34.19 and a P/B of 6.84

- current value of 921 CHF for company B, or a P/E of 9 and a P/B of 0.28

So because of a rate hike, Company A suffers a P/E contraction from 49.35 to 34.19 (i.e -31%) while company B suffers a P/E contraction from 13 to 9, which is also -31%. In this sense, both are equally impacted by the rate hike.

But the capital creation between years 10 and 20 are of 19’906 CHF for company A (i.e 86% of final capital) while only 1’721 CHF for company B (i.e 27% of final capital). This is why for good companies, most of the value occurs in the future while for bad companies the value is in the near term.

But for me, both companies will suffer the same interest rate risk. I would even dare to say that company B might suffer even more, as usually bad companies have lots of debt and might have to refinance themselves at unfavorable terms…

Nice! I’d like to hear what @TeaCup has to say about it. I would intuitively like to believe it’s like TeaCup says, and there is no inefficiency in the market. Buy VT, forget about it. But I’m too weak to find a hole in Julainek’s logic.

It’s an important topic. After all, if great recent performance of quality stocks was due to lowering interest rates, then it’s like sitting on a time bomb. Is the whole philosophy of Terry Smith & Fundsmith not based on quality stocks?

I think he was specifically talking about the backtesting that your graph showed as going back to 2001. MSCI must have done the same kind of backtesting before releasing their new products… so the only way for those new funds to even exist is if they (randomly?) backtested positively.

So it doesn’t make sense to check anything before the release date of that fund.

I did the same maths and came to the same conclusion!

On the other hand the valuation of a start up company will be more sensitive to interest rate increases (negative earnings in the early years, profits in later years)

The article below describes how the propensity of investors to gamble on such companies may be a reason why a quality strategy could outperform: Mr Market is attributing too high valuation to Risky companies relative to Quality companies

Perhaps we are mixing definitions. Quality for me means safe companies with growing profits. Example Microsoft. The opposite would be risky companies which might not yet make profit but attract investment in the expectation of future profits. Let’s say Airbnb which is about to IPO

The article argues that investors go for the big wins and bet too much on risky companies at the expense of quality. The argument would be that Quality companies are undervalued (relatively) which is why excess returns might be made (dot com boom and Warren Buffet?)

In the event of interest rate increases quality companies are making steady profits now. I would even argue their Share price should fall less relative to loss making risk companies

In that article they mention Vanguard’s quality factor ETFs which I didn’t even know existed as one can not find them in their “standard” ETFs list where VT is listed for example. With a search I could find these and first I notice that they are all pretty new and do not seem interesting at all… Most probably because they are too new and have to prove themselves first. It is also very interesting to read that Vanguard themselves call these active managed (Quote: “Factor-based funds are a form of active management.”). So this is enough for me to stay away although TER for most of them are not really higher than what we know from Vanguard. I like also that they really warn you about these factor ETFs.

In case anyone is interested to have a look here is the directly link:

Thanks for the link, I’ve looked for it myself, but failed. The TER is not that bad: 0.13%, it’s US only, so that makes it cheaper. But it’s funny how they say: be aware of the risk, know what you’re doing, this should be not the core of your portfolio. And then you check the multifactor one, and it had a negative performance since inception in 2018, while the market has had 12%.

But it will be interesting to check it again in a few years.

I’m lost in the numbers. Your experience in the topic clearly is way higher than mine and I can’t understand it. What should I look at, which cells to compare? What is the purpose of the Comp 10% RoE & Comp 12% RoE columns, are these all 4 different companies? Why are you comparing discounting rates of 8% and 10%, are these realistic values? Discounting rate is “my best alternative option” or “what the market can give me”, right? How does this correspond to interest rate? I though we’re trying to show the impact of interest rate change on stock valuation?

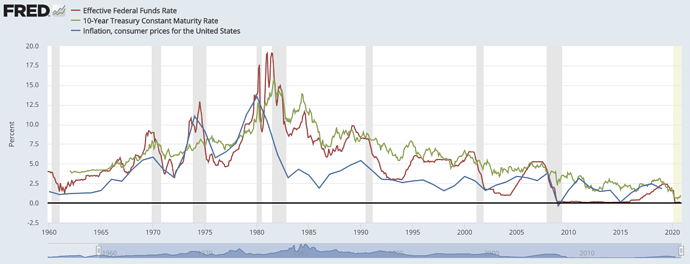

OK but what kind of interest rate are we talking about exactly? Is it the federal funds rate, the treasury rate, or the risk-free rate of return? Just want to understand what am I looking at, as an investor, if the “interest rate” changes from 8% to 10%. How high is it now, by the way?

That’s extremely interesting to me. I will repeat my question: do you think Terry Smith & Fundsmith invest in quality stocks, ergo: are they potentially at risk here?

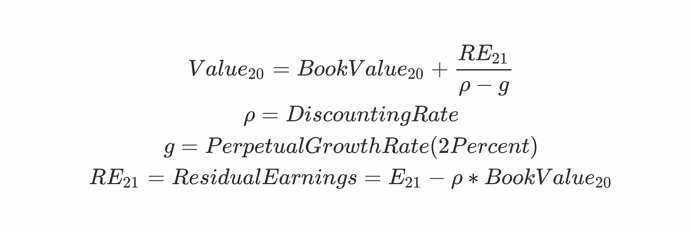

So as said above, Teacup, rightfully said that we should include the perpetual value of the earnings in the computation, since listed companies are expected to last “forever”. This adds a bit of complexity to the maths, so i will give further details so that we are not only two persons to follow the calculation.

In my previous example, i had said to simplify that the value of the business would be the equity realized in year 20, discounted to its present value.

By the way, small digression:

This is the rate of return that the market is asking to invest in a particular company. When analysts forecast future earnings, and the market is asking a certain price, you can reverse-engineer the DCF to figure out what kind of returns the market is expecting. When you look historically, the equity market returned 7%. Here in my examples i have set them randomly to 8% or 10%. More on this later.

So back to the subject, i had simplified too much by saying:

Value at year 20 = Equity at year 20, and you just need to discount it at 8% (or 10% depending on the scenario) to get at the present value.

But indeed we should add the perpetual value of residual earning. So the formula is:

This means we add to the equity the value of the residual earnings growing at 2% in perpetuity.

Take care to not confuse “earnings” and “residual earnings”.

Earnings are the profits that a company is reporting.

Residual earnings are the profits in excess of what the company would have reported if it only earned the required rate of return (i.e 8% or 10%) on its equity.

This is because a company that only earns the required rate of return on its equity is only worth its … equity. This is complicated to read, but easier with an example:

- let’s assume the required return is 10%

- you have an asset with a book value or 100 now, expected to compound at 10% .

Well, something that compounds at 10% and is then discounted at 10% is worth its current book value. Only if it compounds at more than 10% would it add value to the book value. Inversely, if it compounds at less than 10% it would subtract value to the book value. This is the concept of residual earnings.

Those who wants more details on this can read the two following excellent books by Stephen Penman:

- Accounting for Value

- Financial Statement Analysis and Security Valuation

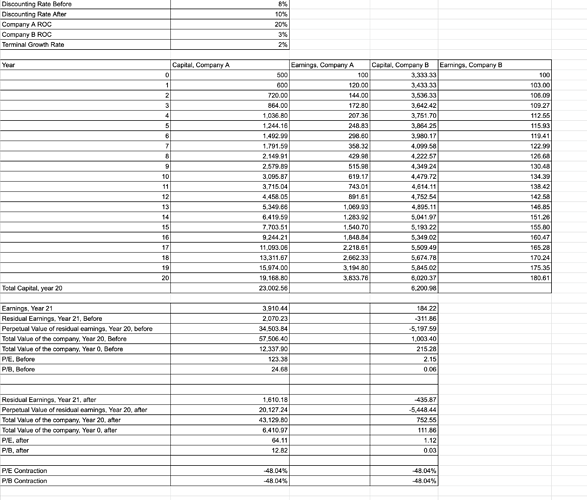

Ok, so back to the examples.

In my previous comparison, i had stopped with the equity in year 20 for both good businesses and bad businesses. We will assume, as TeaCup did in his calculation, that afterward both companies grow only at the rate of inflation, something like 2%.

To get the perpetual value of the residual earnings, you need to do the following steps:

- Compute Earnings in year 21 = Earnings in year 20 * 1.02

- Compute Residual Earnings in year 21 = Earnings in year 21 - discounting rate * book value in year 20

- Divide residual earnings by (discounting rate - growth rate) to get at the perpetual value of residual earnings

- Add book value to perpetual value to get the total value of the company in year 20

- Discount the total at the present year.

So back with our two companies. Company A earns 20% on capital for 20 years, and then matures and grow only at 2%. Company B earns 3% on capital for 20 years, and then matures as well and grow in perpetuity at 2%.

I show below how a rate hike from 8% (before) to 10% (after) impacts the valuation of both businesses:

So now, with a discounting rate of 8%,

- Company A is valued at 12’337 CHF, i.e P/E = 123.38 and P/E = 24.68

- Company B is valued at 215 CHF, i.e P/E = 2.15 and P/B = 0.06

By the way, @Bojack, this should read as “If Company A has indeed these expected earnings, then you will make 8% per year by buying it at a P/E of 123.38”.

You can clearly see the role of residual earning adding to value of company A, and crushing the value of Company B.

Now if the market suddenly asks a rate of 10%:

- Company A is valued at 6’410 CHF, i.e P/E = 64.11 and P/E = 12.82

- Company B is valued at 111.86 CHF, i.e P/E = 1.12 and P/B = 0.03

Both companies will have a compression in value that is bigger than in my previous example, however this compression is again the same:

- Company A has a value going from 12’337 CHF to 6’410 CHF, i.e a compression of -48%

- Company B has a value going from 215 CHF to 111.86 CHF, i.e a similar compression of -48%

@TeaCup, the error in your calculation is that you mixed book value with simple earnings, and not residual earnings.

For me there is no additional interest risk in buying good businesses.

Well this works in theory, but reality shows that there are plenty of businesses not earning their cost of capital (airlines, carmakers…) and are still in business against this logic.

I would be surprised if Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, MSCI, Visa, etc. stop suddenly to be good businesses in the next 20 years. Especially for the two first ones. If the poisonous ratings in 2008 did not kill them, nothing in the near future will.

I asked for numbers and that request has really been taken seriously

I won’t pretend that I understand it all, I’ve never done these kinds of calculations, though it sounds like an interesting skill.

So, just to clarify, when can an interest rate, that the market expects, go up from 8% to 10%? Is a change like this a result of some positive or negative event? (I guess negative, since it slices stock prices by half)

Is it possible to determine what the current rate is? Is it the interest rate that influences the stock prices, or is it the other way round? It seems like small movements in interest rate correlate with big stock price changes.

Well people tend to disagree a lot about which rate to use:

- a simple approach would be to take the historical long term returns of the market, i.e around 7%

- Academics and adepts of CAPM and EMH would tell that the rate is equal to the risk free rate + beta * risk premium (good luck with estimating accurately those values)

- I tend to think that we should simply use the opportunity cost of our second best alternative.

Interest rates influence the price of ALL asset classes.

Now you start to realise why I strongly dislike purely quantitative methods like the DCF. With a subtle change of assumptions in interest rates, compounding rate and period of compounding, an analyst can literally justify any valuation. More to that later.That is the perfect tool for a sell side analyst.

I am happy we cleared the interest rate risk topic.

Regarding what you call an alpha play, this is exactly my thesis since the beginning:

I assert that the market tends to systematically under-estimate how long a good business can enjoy its favourable competitive environment.

This certainly goes against the efficient market hypothesis, no question about it.

Just to give an idea of the order of magnitude that the compounding period plays in the valuation of a company, have look at the following table. It gives the value of a fair P/E, based on the compounding rate and the compounding period length, discounted at 7% (the historical long term market returns):

| Compounding Period: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compounding rate: | 10 Years, P/E: | 20 Years, P/E: |

| 10% | 22 | 28 |

| 12% | 26 | 41 |

| 15% | 35 | 73 |

| 20% | 56 | 178 |

This should read as: “If a company compounds at a rate of 15% for 10 years, then a fair P/E should be 35. If it manages to compound this way for 20 years, then a fair P/E is 73.”

Note the strong difference: in most cases you have a x2 or x3 between the different values.

It is my opinion that, instead of trying to plug some parameters in a model that is ultra-sensible to its input (and thus will be very precise, but not accurate at all), the single best two questions that an analyst should ask (and that would yield 80% of the results of the analysis) is:

- What are the qualitative factors that this company enjoys in its competitive environment?

- How likely are these factors to still be present in ten years?

Clearly, when I see that most analysts focus on next quarter’s EPS, this is not what is happening in the institutional investing world. The two questions above are qualitative and you cannot put a number on them, but that does not mean they are not important…

OK. Just from what I remember in Ben Felix videos, each of the risk factors offers an established risk premium (we have seen that it exists) that the investors get for the additional risk taken. This means, that each factor comes with its own set of risk. So the question remains: what kind of extra hidden risk do quality companies hold? It is very counter-intuitive, it would appear that quality is the opposite of risk. I guess you claim that there is no added risk and the market is inefficient. I would prefer that to be untrue.

By the way, I’d like to better understand what “risk” means when talking about investing and about risk factors. It has been told, that risk is not volatility, and it probably does not even correlate much with it. You could have a boring state bond, that pays a coupon for 30 years, but one of these years the state could go bankrupt and not pay back the principal.

So if I should try to visualize risk, I would try with an example. If there is an investment where you put $100 and with 99% chance you get $105 and with 1% chance you get $0, then I consider this low risk. You then have an expected return of 3.95%.

If on the other hand you invest $100 and with 90% you get $120 and with 10% you get $0, I consider this high risk.

But it’s for sure more complex. How can risk manifest itself?

where do you have your plan, if I may ask?

Just read through this topic and I am super thankful for @Julianek for opening this thread and all the other people who responded.

Do you guys know if we can have any of these products in a retirement vehicle in CH (as in: 3a)?

These are the links that were mentioned as “Quality” tracking products in this thread:

- https://www.amundietf.fr/professional/product/view/LU1681041890

- https://finpension.ch/app/uploads/factsheets/CH0253609066_fact-sheet_de.pdf

- https://www.ishares.com/us/products/272821/ishares-msci-global-multi-factor-etf

- https://www.ubs.com/nl/en/asset-management/etf-institutional/etf-products/etf-product-detail.nl.en.ie00bx7rrj27.basedata.html

A few words about index investing from our fellow Australian pothead Youtuber.

He makes a bet that the S&P 500 and similar passive indexes will deliver poor returns due to disruptive startups (like Tesla). He makes it extra clear that he wants to be held accountable for these words. What do you think? Is this time different? Are the 2020s going to be a transformatory decade where many of today’s businesses will cease to exist? Or is he just blinded by his TSLA lucky shot (his net worth recently exceeded $3 million)

I disagree. If you own a total index including small caps, you’ll get some returns.

A lot of VC funds invests millions in startups and their total returns are quite close to the stock market.

Nobody knows the next winner.

Do you think you are better than them?

Would you be ready today to invest half of your money in a small-cap company thinking it could be the next Tesla?

Sure sure, but we’re not talking about what has been, but what will happen. I wonder if the market return will be “good enough”. I find it interesting when a person goes publicly on the record and makes such a bold statement. You can easily reject him and say he has no idea what he’s saying. Yet, he has already made enough money to retire. Maybe his confidence just comes from luck.