Thank you for noticing this, i had totally missed it. Although it makes my point a bit weaker, I still think that it is remarkable that:

- Buffett (arguably one of the greatest investors over the last 60 years) says in his letters since the 70s that the number one criteria to look for is return on capital

- 40 years later, when we say “Wait a second, what would actually have happened if we had followed his advice”, we end up with a very fine result, even if backtested.

I’ll grant you that. I will rename the topic from “passive” to “index fund”. The approach i am trying to follow here is to ask:

- The first step (totally passive) is to say that I do not know anything.

- But then, is there a single decision that could dramatically improve results? Thinking from first principle, what drives wealth over the long term? I’d argue that a consistent high return on capital comes pretty close to that.

You only need a database of 10-K filings (or local equivalents) to be able to compute a return on capital, growth rate and financial leverage. The factsheet says that the index is rebalanced every six months based on these criteria.

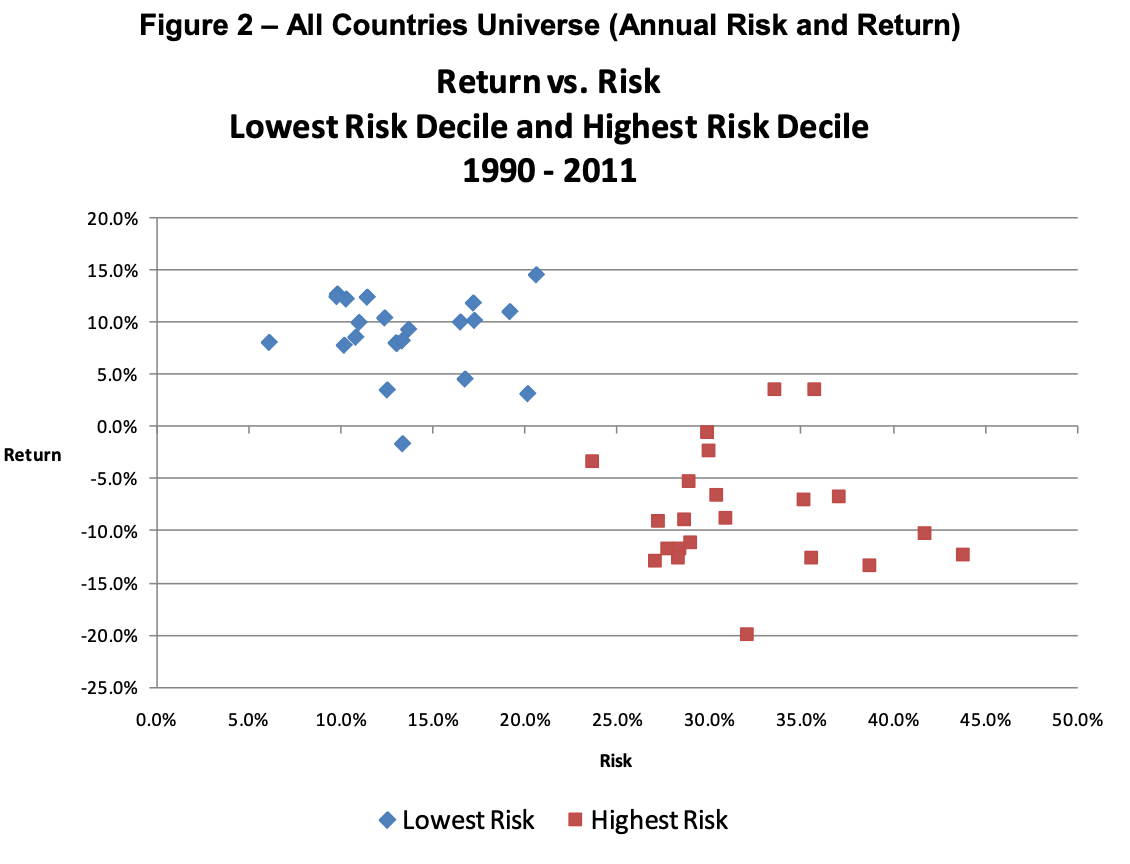

I like Ben Felix but sometimes he should not rely so heavily on modern portfolio theory. MPT works in some cases, and not at all in others. For instance, in this study, Baker and Haugen showed that low-risk stocks (as measured by volatility) consistently over-perform high risk stocks in every developed market.

Someone will try to find a new factor to explain the anomaly and make the French-Fama model consistent, but at some point it is better to ask if you cannot start again on a better basis.

I already touched on a few points here, but there are two kinds of explanation:

- Cognitive biases, such as:

- Hyperbolic discounting bias, where we value short term returns over long term ones

- the fact that the human brain works in a logarithmic way and is incapable to grasp exponential growth

- But mainly, i think there is a structural issue with how the industry and analysts evaluate stocks. Let me explain.

You might know that the number one valuation method to evaluate a business is the discounted cash flow analysis. Analysts try to forecast the cash flow for the next few years, after which they say that they don’t know what’s going to happen so they assign a GDP growth rate in perpetuity after 5 or 10 years. That is to say, they assume that after 5 or 10 years, the business is going to grow at the same rate than the economy, i.e not a lot. That means that each of the forecasted year will have its discounted cash flow, and after that they will add what we call the Terminal Value, i.e the value of all the cash flows after the period of projection.

The vast majority of analysts will use 5-year or 10-year DCF models to value a company and pay painstaking attention to the assumptions to drive their interim period cash flows. If you do yourself the exercise, you will notice something interesting. Here is the contribution of the terminal value to the appraised value of the firm given different interim growth rates in a 10-year DCF model:

| Projection Period Growth Rate | Terminal Value Contribution |

|---|---|

| 5% | 73% |

| 10% | 78% |

| 15% | 82% |

| 20% | 85% |

| 25% | 87% |

| 30% | 89% |

In other words, what happens before the 10 years only weights for 11% to 27% of the company. What is 11%-27%? A margin of error. You can get the next 10 years of projections wrong- as long as you know what the company will look like 20 years from now.

This has a lot of implications:

- Again, people use 5-year or 10-year DCF models where they model in high growth rates and high rates of return. At the end of the “projection period”, they will plug in a perpetual 2% growth rate to the then “boring” company. What if a company can compound capital at a higher rate than its competitors for longer than that? A junior analyst will get laughed out of the room for creating a 20 or 30-year DCF, so again, unfortunate situation for the junior analyst but an opportunity for investors.

- If you follow financial news, you will notice that experts and Wall Street all focus on next quarter EPS expectation. This is all noise and is irrelevant. First, next quarter EPS weight close to nothing in the value of the business. Second, remember that instead of focusing on EPS, you should ask if the profitability of the business has not been impaired.

- Now that you know that most of the value of a business lies in what happens after 10 years, next time you see a -30% drawdown like we had in march, if you believe that the business has the balance sheet to survive, you should pounce on the occasion.

This is another topic, but this comes down to the qualitative analysis of the competitive environment of the business and its competitive advantage (i.e “moat”). Maybe at some point i will do another thread on the subject.