I have recently fixed my collar option strategy (long collar, with e.g. the underlying at 100 you buy a put at 95 and sell a call at 105; the synthetic equivalent would be a bull vertical spread), to roughly lock-in my current +20% YTD return on my main portfolio. Admittedly this is largely market timing looking at the European industry, the upcoming US election and the potential AI bubble and hence not something to recommend. However, it is also an attempt at reducing the volatility of my portfolio, something I have done before very occasionally but never systematically or with an actual logic.

Having recently discussed the sequence of return risk (SRR), I mentioned that I use my own approach of a yield shield strategy (aiming for an FI portfolio of which the passive income covers a lower lean FI target). Alternatively, there is also the standard equity glidepath strategy where you retire with at least a temporary higher bond allocation. The later doesn’t work for me because I don’t link being FI with triggering RE, and don’t want to miss out on the higher expected equity returns long-term.

But now I wonder: Why not systematically hedge portfolio volatility and hence reduce the SRR?

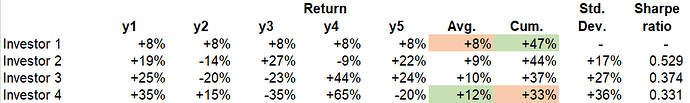

Theory teaches us that volatility is just as important as returns. As an example:

These are all quite bad portfolios with a Sharpe-ratio (avg. return/std. deviation of returns) below 1, but it shows an example of an inverse correlation between annual average return and cumulative return. The best portfolio is the steady +8% annual of investor 1, the worst the high flying +12% annual of investor 4 because the severe drawdowns kill the cumulative performance.

The contra argument is simple: Hedging is usually not free (a put certainly isn’t and even though a collar option strategy can be free, it still creates opportunity cost long-term), and would inevitably reduce the expected annual return. You would also need to have a somewhat sophisticated understanding of the characteristics of your portfolio to engage in proper hedging, which is not typically given (i.e. it may be a lot of work).

What I am considering is to define a collar option strategy to follow continuously. Something like a simple rule where at X% performance you hedge Y% of your portfolio (e.g. at rolling 12-month performance one standard deviation above long-term expected return you hedge 50% of the portfolio).

Is anyone doing something like that or has an opinion on this? Specifically, I wonder:

- Would you do this on a continuous 12 month rolling basis? Because obviously there is no argument for a YTD approach.

- How would it work on the downside? With nice unrealized returns it feels quite simple, but logically you would also hedge in a loss scenario (though maybe not as collar which cuts the upside).

- How could one approach this to define what levels make sense to hedge and define such a rule? So far, I am acting purely on gut feeling.