So what of the gliding path toward retirement?

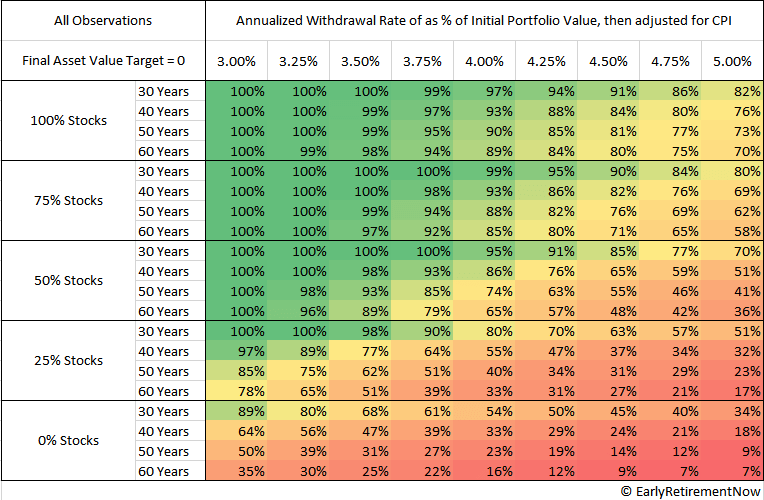

Past results are no guarantee for the future, and while Big Ern studies show that a 100% allocation to stocks should be perfectly acceptable for a retirement strategy using a 3.5% SWR (though 75/25 seems to be better overall), this is math. The results assume someone applying mechanically the 4% SWR rules, but we are human beings: watching our portfolio get depleted with no more additional capital to compensate for it can be gruesome and give way to behavioral errors, or simply very, very bad nights (with potential health consequences… silver lining: having a fatal stroke before the portfolio gets depleted means it actually did suffice to fund retirement, if you’re into that kind of thinking. That’s not the outcome I’m aiming for myself and I intend to sleep well and enjoy life for as long as I will be able to).

Psychology trumps math, hence risk tolerance assessment, hence the search for a balance between return and volatility of the portfolio, hence bonds (and other asset classes).

As we start our professional career, human capital is all we have. Since we have close to no financial capital to loose, taking risks is a very attractive option and loosing it all only means we would start again. Winning brings big rewards, loosing only means you’re back at the start, as a still young person with a lot of human capital. At this point, the new contributions trump the variations in the market and big markets downturns have lesser psychological impact on us. Investing in riskier assets is easier.

As we age, we gather financial assets and loose human capital. At some point, our invested assets are largely more important than new contributions and the variations of the portfolio value start to have more of an impact. On top of that, retirement gets closer and we think more about the money we’ll have to withdraw from the portfolio then. At this point, it is very likely that our risk tolerance changes and that a more conservative allocation starts making more sense.

Finally, at the door of retirement and afterwards, we suddenly cease getting any new contribution coming from our work. Whatever we have is all we have to endure until our death, knowing that less healthy days and bigger medical and elder care expenses are probably coming further down the road. Some people can take it, most probably need more safety to be able to enjoy life without getting anxious every time the market gets a hiccup, or even worse, a real crash.

At that point, bonds serve 2 purposes:

-

they hopefully reduce the portfolio volatility (yes, I know, 2022 doesn’t quite follow that path, more on that in a future post).

-

they hopefully provide a stable reserve of funds able to finance future expenses for an acceptable amount of time (make it 10-15 years, for example). And yes, I know, hello 2022 again!

Which brings us to the actual question of the OP: how to craft our gliding path?

First, there are other ways to consider retirement funding than the 4% rule. I’ll keep it for another post but keep in mind that the 4% rule is more guidance than rule, nobody follows it to a T anyway.

Second, several bits of guidance have been given:

Jack Bogle, the father of Index investing, suggest that “age in bonds” is a good starting point to ponder on the gliding path toward retirement.

Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffet’s inspirational figure, states that “the investor should never have less than 25% or more than 75% of his funds in common stocks.”

There are advocates that say that given our longer life expectancy than our ancestors, a change to the “age in bonds” guideline, toward a 110-age in stocks or 120-age in stocks makes sense.

As suggested by nabahlzbhf, checking the Vanguard target retirement funds gives an example. They seem to start off more agressively (11% bonds for a fund aimed at people of age 19-25), then trend toward age in bonds, with a cap (71% bonds for people age 75 and older).

That being said, I’d pay attention to recency bia when reading on the recent advice geared toward more agressive allocations. While some of it is rooted in truth (Big Ern studies, for example), we’re getting out of a period of incredible returns for stocks and until very recently, bonds yielded close to nothing (when not negative), so it’s easy to diss out bonds and think that stocks is all you need.

As stated above, there are several different ways to look at funding retirement spending and there are a slew of strategies to address it, I’ll get more into it in a further post but for now, I’ll simply mention:

-

liability matching ladder of bonds: since, baring bankruptcy, the amount of principal paid back by bonds at maturity is known in advance, we can purchase our bonds to make it that an amount matching our expected expenses achieves maturity every year, only drawing on stocks to build more year ladders.

-

risk parity portfolios: there is more to the investing world than just total market stocks and bonds. By mixing a broader set of assets, mixed with factor investing and mixing bonds durations, one can aim to achieve a “permanent” portfolio, that should maximize risk adjusted returns and terminate the need for a bonds glidepath. Harry Brown’s Permanent Portfolio, Ray Dalio’s All Weather Portfolio (though it’s interesting to note that Ray Dalio currently thinks that bonds, which make up 55% of the All Weather, are trash and that investing in EM is the future…) and the Golden Butterfly are among those.

-

some people like to increase their bond allocation before retirement, then live off it for the first years, gradually decreasing it until reaching their target retirement allocation (bond tent).

Also to note and maybe the most important part of this post: retirement planning is very personal. There is no “one-size fits all”. Only you know yourself, your needs, your wants, the people you want to support and those who can support you, etc. Guidelines are nice to take a quick decision and buy time for more in depth considerations and to help give directions to said considerations but you are unique and should do what works for you.

![]() ? Of course, that’s not moving away from stocks.

? Of course, that’s not moving away from stocks.