Today’s Matt Levine edition about Credit Suisse (here)is really really good. In particular the explanation about AT1 Bonds:

AT1s

After the 2008 financial crisis, European banks issued a lot of what are called “additional tier 1 capital securities,” or “contingent convertibles,” or AT1s or CoCos. The way an AT1 works is like this:

- It is a bond, has a fixed face amount, and pays regular interest.

- It is perpetual — the bank never has to pay it back — but the bank can pay it back after five years, and generally does.

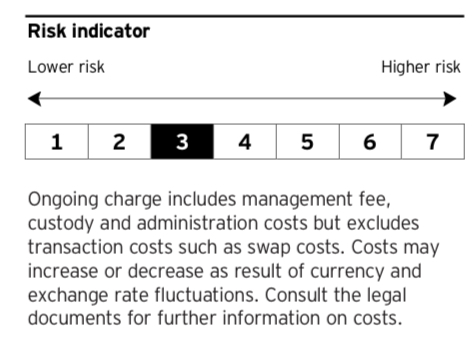

- If the bank’s common equity tier 1 capital ratio — a measure of its regulatory capital — ffalls below 7%, then the AT1 is written down to zero: It never needs to be paid back; it just goes away completely.

This — a “7% trigger permanent write-down AT1” — is not the only way for an AT1 to work, though it is the way that Credit Suisse’s AT1s worked. Some AT1s have different triggers. Some AT1s convert into common stock when the trigger is hit, instead of being written down to zero; others are temporarily written down (they stop paying interest) when the trigger is hit, but can bounce back if the equity recovers. (Here is a 2013 primer on CoCos from the Bank for International Settlements.)

These securities are, basically, a trick. To investors, they seem like bonds: They pay interest, get paid back in five years, feel pretty safe. To regulators, they seem like equity: If the bank runs into trouble, it can raise capital by zeroing the AT1s. If investors think they are bonds and regulators think they are equity, somebody is wrong. The investors are wrong.

In particular, investors seem to think that AT1s are senior to equity, and that the common stock needs to go to zero before the AT1s suffer any losses. But this is not quite right. You can tell because the whole point of the AT1s is that they go to zero if the common equity tier 1 capital ratio falls below 7%. Like, imagine a bank:

- It has $1 billion of assets (also $1 billion of regulatory risk-weighted assets). 6

- It has $100 million of common equity (also $100 million of regulatory common equity tier 1 capital).

- It has a 10% CET1 capital ratio.

- It also has $50 million of AT1s with a 7% write-down trigger, and $850 million of more senior liabilities.

This bank runs into trouble and the value of its assets falls to $950 million. What happens? Well, under the very straightforward terms of the AT1s — not some weird fine print in the back of the prospectus, but right in the name “7% CET1 trigger write-down AT1” — this is what happens:

- It has $950 million of assets and $50 million of common equity, for a CET1 ratio of 5.3%.

- This is below 7%, so the AT1s are triggered and written down to zero.

- Now it has $950 million of assets, $850 million of liabilities, and thus $100 million of shareholders’ equity.

- Now it has a CET1 ratio of 10.5%: The writedown of the AT1s has restored the bank’s equity capital ratios.

This, again, is very explicitly the whole thing that the AT1 is supposed to do, this is its main function, this is the AT1 working exactly as advertised. But notice that in this simple example the bank has $950 million of assets, $850 million of liabilities and $100 million of shareholders’ equity. This means that the common stock still has value. The common shareholders still own shares worth $100 million, even as the AT1s are now permanently worth zero.

The AT1s are junior to the common stock. Not all the time, and there are scenarios (instant descent into bankruptcy) where the AT1s get paid ahead of the common. But the most basic function of the AT1 is to go to zero while the bank is a going concern with positive equity value, meaning that its function is to go to zero before the common stock does.

Credit Suisse has issued a bunch of AT1s over the years; as of last week it had about CHF 16 billion outstanding. Here is a prospectus for one of them, a $2 billion US dollar 7.5% AT1 issued in 2018. “7.500 per cent. Perpetual Tier 1 Contingent Write-down Capital Notes,” they are called.

In UBS’s deal to buy Credit Suisse, shareholders are getting something (about CHF 3 billion worth of Credit Suisse shares) and Credit Suisse’s AT1 holders are getting nothing: The Credit Suisse AT1 securities are getting zeroed. This is not, to be clear, exactly because Credit Suisse’s CET1 capital fell below 7%; instead, there is a separate clause of the AT1s allowing them to be zeroed if the bank’s regulator decides that zeroing them is “an essential requirement to prevent CSG from becoming insolvent, bankrupt or unable to pay a material part of its debts as they fall due.” 7 Plus, in a situation like this, the banking regulators get to do a certain amount of ad hoc stuff, and they do. (They got rid of the shareholder vote on the deal!) Zeroing the AT1s while preserving a little value for the common does seem to have been done in an ad hoc way; my point is just that it follows very logically from the terms and function of the AT1s.

People are very angry about this. Bloomberg News reports:

The clauses that led to the bonds being marked to zero aren’t common. Only the AT1 bonds of Credit Suisse and UBS Group AG have language in their terms that allows for a permanent write-down and most other banks in Europe and the UK have more protections, according to Jeroen Julius, a credit analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. …

“This just makes no sense,” said Patrik Kauffmann, a fixed-income portfolio manager at Aquila Asset Management, who holds Credit Suisse CoCos. “Shareholders should get zero” because “it’s crystal clear that AT1s are senior to stocks.”

The Financial Times adds:

“In my eyes, this is against the law,” said Patrik Kauffman, a fund manager at Aquila Asset Management, who invests in additional tier 1 (AT1) bank debt.

He said it was “insane” that under the terms of UBS’s takeover of Credit Suisse, AT1 bondholders were set to receive nothing while shareholders would walk away with SFr3bn ($3.2bn). “We’ve never seen this before. I don’t think this would be allowed to happen again.”

Davide Serra, founder and chief executive of Algebris Investments, said the move was a “policy mistake” by the Swiss authorities. “They changed the law and they have basically stolen $16bn of bonds”, he said in a widely attended call on Monday morning.

I’m sorry but I do not understand this position! The point of this AT1 is that if the bank has too little equity (but not zero!), the AT1 gets zeroed to rebuild equity! That’s why Credit Suisse issued it, it’s why regulators wanted it, and it would be weird not to use it here.

Oh, fine, I understand the position a little. The position is “bonds are senior to stock.” The AT1s are bonds, so people bought them expecting them to get paid ahead of the stock in every scenario. They ignored the fact that it was crystal clear from the terms of the AT1 contract and even from the name that there were scenarios where the stock would have value and the AT1s would get zeroed, because they had the simple heuristic that bonds are always senior to stock.

That’s the trick! The trick of the AT1s — the reason that banks and regulators like them — is that they are equity, and they say they are equity, and they are totally clear and transparent about how they work, but investors assume that they are bonds. You go to investors and say “would you like to buy a bond that goes to zero before the common stock does” and the investors say “sure I’d love to buy a bond, that could never go to zero before the common stock does,” and the bank benefits from the misunderstanding.

We talked about CoCos a few years ago due to a different misunderstanding. CoCos generally are perpetual — they never need to be paid back — but the bank is allowed to repay them after, usually, five years (the “first call date”). It is customary for banks to repay CoCos at the first call date (because they are like bonds), but it is not required, and in fact bank regulators go around saying that banks shouldn’t make too much of a habit of repaying them. “A bank must not do anything which creates an expectation that the call will be exercised,” say the rules, because the regulators do not want CoCos to be too bond-like.

And so one day four years ago Banco Santander SA did not call its AT1s after five years, and the market freaked out. “Santander’s decision is raising questions about whether investors will start souring on AT1s across the board,” said the Wall Street Journal at the time, “which could force European banks to rethink a key way in which they have cushioned themselves against potentially catastrophic losses since the global financial crisis.” I was unmoved. I wrote:

If the regulators think that AT1s are equity and the investors think that they’re debt, someone is wrong, and much better for the investors to be wrong!

Since then I have become very convinced that regulators know how AT1s work, and that investors don’t, and that this is good.

Anyway there are once again threats that this is the end of the AT1 market, that no one will ever buy these securities again, etc., threats that are familiar from the Santander situation four years ago. Bloomberg:

Market participants say the move will likely lead to a disruptive industry-wide repricing. The market for new AT1 bonds will likely go into deep freeze and the cost of risky bank funding risks jumping higher given the regulatory decision caught some creditors off-guard, say traders.

That would give bank treasurers fewer options to raise capital at a time of market stress, with the Federal Reserve and five other central banks announcing coordinated action on Sunday to boost dollar liquidity.

And my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Marcus Ashworth:

The entire banking sector will end up paying for Credit Suisse’s myriad transgressions one way or another. The repercussions of the Swiss takeover structure may close off access to CoCos for all but the strongest banks — the definition of which will come under ever-closer scrutiny.

To be fair, most AT1s outside of Switzerland don’t work like this — they tend not to be permanent write-down AT1s — and so it is not clear why the Credit Suisse writedown should affect the prices of other AT1s:

European regulators are rushing to reassure investors that shareholders should face losses before bondholders after the takeover of Credit Suisse Group AG wiped the bank’s Additional Tier 1 debt.

The clauses that led to the bonds being marked to zero aren’t common. Only the AT1 bonds of Credit Suisse and UBS Group AG have language in their terms that allows for a permanent write-down and most other banks in Europe and the UK have more protections, according to Jeroen Julius, a credit analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

It is just possible that the explanation is that AT1 investors don’t read the terms of their securities? Anyway European Union and UK banking authorities put out statements saying in effect that they would never do what the Swiss authorities did here, and that (in the Bank of England’s words) “AT1 instruments rank ahead of CET1 and behind T2 in the hierarchy. Holders of such instruments should expect to be exposed to losses in resolution or insolvency in the order of their positions in this hierarchy.” If you read that very closely, it does not quite say that AT1 instruments can’t be written off in a shotgun merger over the weekend that preserves some value for the equity (not “resolution or insolvency”!), but I guess there’s no reason to read it too closely.