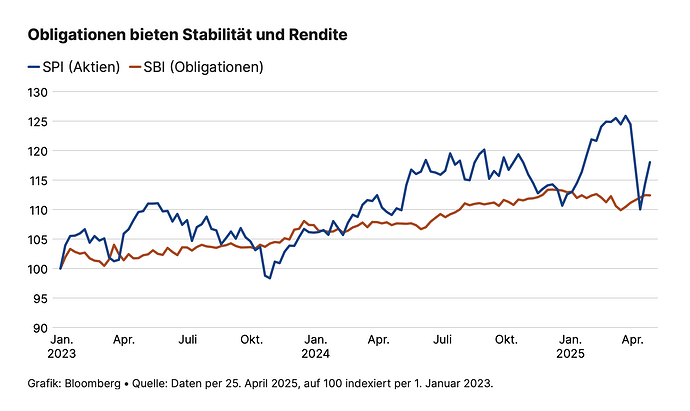

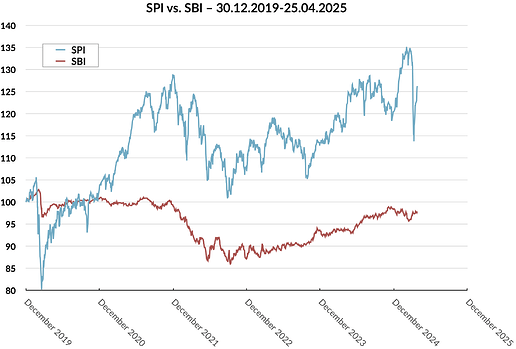

You can change almost any return comparison by picking different starting points.

However, this sword cuts both ways: if you want to invest today, you’re also picking a starting point … might be the one where blue outperforms red or vice versa or both remain flat.

(Given long enough time frames we all know of course that equities outperform bonds)*

* At least for the (very few) markets/countries I am familiar with.

Narrator (aka Chat-GPT) puts Goofy to shame:

"Yes, there have been markets and time periods where bonds outperformed equities over 5 years or more, especially during times of:

- Severe equity underperformance (e.g., crashes, lost decades),

- Falling interest rates (which boost bond prices),

- Or deflationary environments.

Examples:

Japan – The “Lost Decades” (1990s–present)

Japan – The “Lost Decades” (1990s–present)

After the stock market crash in 1989, Japanese equities (e.g., the Nikkei 225) stagnated or declined for decades, while Japanese government bonds (JGBs) delivered positive returns—albeit modest. Over many 5- and even 10-year periods, bonds outperformed equities.

United States – 2000–2010 (“Lost Decade”)

United States – 2000–2010 (“Lost Decade”)

- The S&P 500 delivered negative real returns over this period.

- Meanwhile, U.S. Treasuries and investment-grade bonds performed well, especially during the 2008 financial crisis, when equity markets tanked and investors fled to bonds.

Europe – Various Sovereign Debt Crises

Europe – Various Sovereign Debt Crises

In the Eurozone periphery (e.g., Greece, Italy) during the 2010s, equity markets suffered, while core government bonds (like German bunds) provided better returns during flight-to-safety phases.

Emerging Markets During Currency Crises

Emerging Markets During Currency Crises

In some emerging markets (e.g., Argentina, Russia, Turkey during specific crises), equities collapsed in local or USD terms, while hard currency bonds (like USD-denominated sovereign debt) outperformed over multi-year stretches.

So yes, equities outperform bonds over the very long run (30–50 years) in most markets, but over 5–10 year horizons, especially during crises, bonds can and do outperform."