so is there any rationale left why we should not jest give all out money to buffet?

I am seriously considering allocating a part of my folio in Berkshire. The only questions I want to answer first is :

-Buffett is 86 years old, Munger 93 years old. What happens when they die? How will investors react?

-Berkshire Hathaway has a 419 billion market cap. At which point is this too high to sustain high returns? Due to its size, Buffett has not a lot of stocks to choose from. How does it affect his performance? To keep investors calm, Buffett, has said many times in the recent past that it would be very difficult to achieve returns superior to 10% in the future. Is he being conservative or utterly realistic?

But yeah, in the first chapter of The Manual of Ideas, John Mihaljevic states :

If you want to do active investing, ask yourself if you can do better than Buffett. Otherwise, it would be better to just let him handle your money.

I think that both @1000000CHF and @Julianek have a point. Passive investing is definitely the safer choice. It’s hard to predict which active fund will perform well in the future. And the ones with the proven track record, like Buffett, are old, so forget about him if you want to put your money for 30 years.

But then on the other hand, who is making the buy and sell decisions on the market? You have index funds, who just follow market cap, you have pension funds, who are risk-averse, you have plenty of home-grown investors. The market is very susceptible to hypes and bubbles, because it is a guessing game for most.

So I can imagine how if you have a buy and hold strategy focused on long-term returns, you can follow some principles that will yield better result than the index. I like the principles listed on the Fundsmith factsheet (https://www.fundsmith.co.uk/fund-factsheet). That said, going with an active fund is a risk, a trust matter, and I feel more comfortable with just average returns by an index fund which decisions are made by a simple algorithm.

I apologize if I sounded more harsh or arrogant as I intended to be.

The truth is, I have nothing against passive investing per se. The goal of most of us here is to be financially independent and retire early, and so far passive investing has proven to be a very effective mean to this end.

As such, it is a wonderful tool

But it is only that : a tool. I have problems when people start saying that this is the only valid tool, and that anybody else using successfully a different tool is just lucky. it looks a lot like integrism to me, and I would not like investing discussions looking like political discussions

Passive investing and EMH are powerful tools, but as in other domains, the map is not the territory.

Past history has shown that markets have had periods (1999-2001, 2007-2009) and sectors (micro caps) where they were far from efficient. Some investors have been wise enough to profit from these anomalies, and good for them!

Maybe I overreact, but I like this forum, and I would really like that it does not become like the MMM forum, where any tiny attempt to talk about anything else than passive investing is considered as market timing and thus coming straight from hell…

On the other hand, I fully realize that we are on the passive investing thread, so I will try to refrain myself next time

I also don’t have anything against active investing. I just think it’s unreasonable for 99% of the people. It’s just pure common sense - on the long-run most people will get worse results than the index.

Here’s another interesting podcast on passive investing:

And here’s something special for @Julianek (so that he doesn’t think I’m a religious zealot  ):

):

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audio/2017-07-14/ed-thorp-the-man-who-beat-the-dealer-and-the-market

Thanks for the links!

Regarding Ed Thorp, the guy is truly amazing. His book “A man for all markets” is really enjoyable and interesting, I advise it to everyone

The freakonomics post has a lot of good points. I think there is a lot of important points to emphasize, but some other aspects are missing… I will try to address this in my next posts to come soon (sorry, I cannot resist the urge to comment…  I will try to keep the discussion constructive, rational an non-dogmatic though. Correct me when I am wrong)

I will try to keep the discussion constructive, rational an non-dogmatic though. Correct me when I am wrong)

About the fact that people should go away from most active funds :

I agree with that. Let’s take as an example an average fund with 1 billion USD under management. Let’s further assume that its fees structure is like a regular active fund : 2% of assets and 20% of the performance. We will quickly observe the following :

-

If the fund want a correct diversification, it will look to have around 20 securities in the portfolio. That makes 5% of the portfolio invested in each security, i.e 50 million USD . If the fund does not want to have a significant impact when it buys a share, the company bought should have a significant market capitalisation : the 50 millions USD should not represent more than 3 or 4 % of the market cap. Thus the target company should have at least a 1 billion USD market capitalisation.

This single fact limits most funds to invest in a very restrictive perimeter of around 500 different stocks. We are in a situation where the vast majority of all invested assets are concentrated on a very small perimeter of companies : the big caps.

Of course, this tends to lead to an extreme market efficiency in the big caps funds, and if the market are efficients there most fund managers should get around the market average. This also means that for the retail investor, a lot of opportunities lie in the stocks left on the way by institutional investors.

So our first conclusion is that usually, size is not a friend for the retail investor. -

Let’s compute the fees gained by the manager. He will always earn at least 2% of assets : that is 20 millions USD.

For the performance fees, in the case of a bad year, he will earn nothing, and in a case of a good year (let’s say +15%), he will earn an additional 30 millions USD. So even in the worst case scenario, he already makes 20 millions.

We see already a big issue : about half oh his revenue is not earned by providing value to the investor, but by having assets under management.

Given this incentive, the most logical thing for him to do is not to invest wisely, but to increase his asset base. This is a big conflict of interest! The investment company will spend more resources and time marketing the fund than actually investing.

Furthermore, we have seen in (1) that size is not an advantage for the final client investor : we have two agents having different incentives, and we know perfectly well that the fund manager will win at the end. -

So in most cases, the biggest motivation of a fund manager is to have as much as assets under management. His only fear : losing these assets! This happens when clients withdraw their money. This threat is so strong that the manager does not want to risk to underperform too much : that would be a direct cut in his revenue. Therefore, a lot of managers are herding and don’t go too far from their benchmark. This is a real paradox : officially the funds should try to “beat the market”, but most of them don’t even try. It is much more comfortable to be average and to secure one’s asset base.

(Personal note : In my opinion, this is also why so many statistical studies show the lack of performance of active funds. The lack of performance does not come necessarily from the lack of skills, but rather from the bad incentive for the manager). -

As if the odds where not bad enough, there is an additional constraint : the final client behavior. A lot of clients will want to withdraw their money in a bear market and enter the fund in a bull market. This is the exact opposite of what should rationally happen! In a ideal world, the manager would have plenty of funds to invest when securities are cheap, and would like to sell when they become overvalued. Here we have the exact opposite : he will have to sell low (locking in losses), and buy high (killing then the opportunity for a good return). Buffett understood well this issue and that is why he built Berkshire Hathaway as a holding and not as a fund. When an investor wants to go out, he will just sell his security to another investor. Buffett keeps the money and does not need to give it back to the investor

-

Finally, let’s talk about the few good managers who understand these principles. Usually, they will just have a performance fee. To be able to perform well, they will try to keep assets under management not too big. Unfortunately, to be able to do this they will keep their fund closed to new investors. For instance, in Switzerland, the only too good managers with a proven track record of over-performance on the long term, Guy Spier and John Mihaljevic, have both a fund closed to new investors.

Thus, for all these reasons, we can conclude that

-> Most active funds are not worth getting into

-> The really few good funds are very difficult to get in.

That’s why a retail investor should not bother to pay another person to handle actively his money, because he will surely have

a) mediocre performance

b) hefty additional fees

(at least on this we can agree  )

)

To be continued.

I think there’s simple relation in the active funds: if the manager is good, then he charges more and thus the costs eat the beat-the-market premium. If the managers sucks, he charges less but he can’t beat the market.

But the be frank, I don’t really believe that most individual investors can beat the market as well on the long run. One reason is that if there’re market inefficiencies, then people with more powerful tools are more likely to exploit them and most retail investors don’t have the tools (financial/economic/business knowledge, access to information, software, computing power, etc). The other reason is that over long run market inefficiencies smooth out and the underlying risk factors have more impact on returns. Another reason is that if the net-net picked share is growing, it’s most likely growing because all other shares are growing - but there’s a cost of keeping capital not invested, because you need to have cash reserves prepared for next occasion. I think that in general staying not invested + transaction costs are the main reasons why indexing is more productive on the long run.

But I’d like to see some data comparing the performance of most index individual investors with most shares-picking individual investors (or even most net-net investors). Your performance might be not representative example, because you’re way smarter and talented than most retail investors.

Yes and No. Surely a good manager can charge more fees. But what kind of fees?

I really think that in investing (and in life in general), you get what you reward for. (aka the power of incentives).

Fees based on performance reward good performance and good investor managers.

Fees based on asset size reward bigger asset sizes.

In the first case the incentive for the manager is to be a good investor.

In the second case the incentive for the manager is to grow the asset base, to do a lot of marketing, to be advertised by most investing banks, and above all to not depart from the herd, because it would be too risky if it backfires and client retire their money.

As long as most active funds will have the second type of fees and they are the main component of their revenues, the second behavior will be incentivized and the manager will have a serious conflict of interest against his client. what’s sad is that most clients don’t realize that.

You have valid points but to be able to discuss them fully (and there is the same issue in the freakonomics article), we will need to discuss first :

- To which extent the efficient market hypothesis is valid

- What we define by “investing” and “investor”, because it covers a wide range of interpretations

And I will try to address these concerns in my next posts.

Thanks for the compliment but I really think that my case is more common sense that smartness. I just realized that:

- A stock performance is (among other factors, such as buying price) depending on the underlying business

- The language of business is accounting, thus I should learn corporate accounting

- Most retail investors don’t bother doing it, hence my advantage. People not bothering learning accounting to value a stock are like one-legged men in an asskicking contest, as Munger says

That would actually be an interesting read for me: who pulls the strings on the market, what is the share of each investor group. Whoever they are, I don’t know if they are doing the best job. If the powerful people are making the biggest influence on stock prices, then why do we have bubbles and crashes? The pessimistic answer would be, that they are helping the bubbles grow and know just when to pull out before the crash. But in that case their rate of return would be so high, that by now they should own the world.

I think (just based on intuition) that the market is inefficient enough for a small percent of very smart individual investors to keep beating the market not just by luck.

On the Efficient Market Hypothesis

In the following posts I may play the devil’s advocate, however I hope this will open some constructive discussions and that I will learn a lot more about these subjects

The efficient-market hypothesis is very important because it is the ground basis of the theories used in modern finance as well as in passive investing.

The EMH has been published by Eugene Fama in 1970 and it takes three forms :

- The weak form maintains that past stock prices provide no useful information on the future direction of stock prices. In other words, technical analysis (analysis of past price fluctuations) cannot help investors.

- The semi-strong form says that no published information will help investors to select undervalued securities since the market has already discounted all publicly available information into securities prices.

- The strong form maintains that there is no information, public or private, that would benefit investors. That means that Investing with insider information is useless.

The implication of both the semi-strong and strong forms is that fundamental analysis is vain. Superior returns are due to pure luck and these returns occurred because the investor took more risk.

Now, before discussing the soundness of the EMH, it is worth taking note that its importance is huge in the academic world. Indeed, without the EMH, all the following concepts are flawed :

- The Modern Portfolio Theory

- The Capital Asset Pricing Model, especially terms like „beta“ or „alpha“

- The concept of volatility as a measure of risk

- option pricing models, in particular Black Scholes formula -> It follows that most derivative instruments are not priceable in a direct manner

- …

Efficient Market Hypothesis is very practical and elegant because it allows many economic problems to be mathematically tractable. Thus is is used heavily in academics.

On the other hand, there is the opposite incentive in the investment industry : every fund manager would like to convince us that he he will perform better than average. In this industry almost nobody will tell you that market are efficient.

So, where should we place ourselves? To which extent is the Efficient Market Hypothesis relevant?

-

I believe that the weak form of the EMH is true and that only analyzing past prices evolution of a security to predict its future price is a waste of time. But I would be glad to be wrong! If someone knows a chartist with a successful track record over a prolonged period, I’d be happy to learn more about it.

-

I know from my personal experience that the strong form is plain false. I work in a publicly traded company and there is a reason why we have a compliance department forbidding us to trade shares of our company in the three months preceding the publications of our semi annual results : if we could and have bought or sold the shares of the company one day before each publication (depending if the results are positive or negative), we would have earned at least an easy 15% every six months. But in most countries, insider trading is illegal; so even if the strong form is false, it is no big deal.

-

Now the hardest part to debate : what about the semi-strong form of the hypothesis?Can we really assume that fundamental analysis because any public information is reflected in the price of securities? Can we really think that it is almost impossible to beat the market with skills, and not with luck, without tons of powerful tools and an army of analysts?

I tend to think that it is mostly true in the domain of big and very big capitalisations, like for instance S&P500 companies. It is the area where most institutional funds compete and where the most money is at stake. There are thousands of analysts available to analyse Apple Inc., and I believe that given the stakes, the means and the competition, the prices of big caps should not be too far from their real value.

Note that sometimes it is temporarily not true : for instance, let’s take year 1987. It is a little bit hard to conceive that in that year, according to the stock prices, the american economy’s value raised a wonderful 40% from January to July as measured by the Dow Jones performance. It is even harder to believe that the american economy really lost 23% of its value on a single day on Monday, October 19.

Yahoo’s stock price was 110$ in 2000 (for a $125 billion valuation) but only $15 one year later. It is reasonable to think that at least one of this prices departed from reality.

But all in all, I tend to think that these situations are more a few exceptions that the rule, so in this area of big caps, the EMH looks like a quite acceptable model. For a retail investor, it is thus very difficult to have an edge in the world of Big and Very Big caps.

However, It is my opinion that the farther we go from big caps, the less the markets are efficient. There are around 7000 stocks listed on US markets, and big caps (with a market capitalisation superior to 10bn USD) are only 650 of them. Even if we lower the market capitalization limit to $2Bn, there are only around 1600 stocks above this limit, leaving 5500 stocks where institutional investors are not really eager to participate. There are far ore people analyzing Microsoft Corporation than, let’s say, Vectors Inc (don’t ask me, I’ve chosen this one randomly among small caps).

If we have much less participants, then the mechanism of price discovery is less effective, and inefficiencies start to emerge.

This effect is even more pronounced in the world of micro caps : for instance, it makes absolutely no sense that Rubicon Technology Inc (RBCN) is quoting at least since beginning of 2016 under half its liquid assets minus all debt : that would mean that the company is worth more dead than alive, which is obviously not true.

Add to this the behavior of institutional investors, who are sometimes forced to get rid of assets without regard to their investment merits and can cause stock prices to depart from underlying value.

Institutional selling of a low-priced small-capitalization spinoff, for example, can cause a temporary supply-demand imbalance, resulting in a security becoming undervalued.

If a company fails to declare an expected dividend, institutions restricted to owning only dividend-paying stocks may unload the shares. Bond funds allowed to own only investment-grade debt would dump their holdings of an issue immediately after it was downgraded below BBB by the rating agencies.

When a company enters or leaves an index, a lot of index funds will be forced to buy/sell the stock, regardless of its merits.

Other phenomenas such as year-end tax selling and quarterly window dressing(trades that are here uniquely because you have to provide good quarterly reports) can also cause market inefficiencies.

There is another point I’d like to make. To function correctly, the EMH relies among others on the following axioms:

-

Perfect information and a perfect ability to digest it. Huge blowups like Enron, Lehman Brothers, or Worldcom make me think that it is at least not totally true. I tend to believe that there is so much information that it is quite difficult to process it accurately.

-

People are rational : that is what we would like all to think, and I do not depart from it. However, I encourage every one to read Robert Cialdini, Dan Ariely or Daniel Kahneman to realize that it just is not true, and that we make often far from optimal choices.

-

Everybody has the same incentive : The EMH assumes everyone is seeking the highest risk adjusted returns. But there are many cases in practice where it is not the case :

- Too big too fail institutions : If they win, they keep the money. But if they lose, taxpayers bail them out. That allows for very nice „Risk adjusted „ returns… but a complete misalignment of incentives

- Proprietary traders : traders having no skin in the game : they bet the bank’s money, not their own. If they lose, they’ll end up in another bank. For instance, in 2011 the rogue trader who lost USD 2.4bn at UBS had been doing it for three years. Again, misalignment of incentives, and enough fire power to introduce big inefficiencies.

- Personal goals : As said earlier, the EMH assume everybody looks for the best risk adjusted returns. But I may argue that among the investors population, there are various profile of risk profiles. Can we compare the 60 years old retail investor saving for retirement and having a severe risk intolerance, with an university endowment having an infinite horizon timeline?

Ok, so with these elements we can see that the semi-strong form may be valid in certain domains and times (big caps in non bubble times), but is also far from true in other domains.

But at the end of the day, the question that interests us is :

„If the EMH is false, why aren’t there so many active investors beating the market?“

I’ll start first by dividing active investors between retail and institutional investors and will address each individually :

- Retail investors : Let’s make the following observations : how many retail investors bother learning the proper tools of investing, for instance accounting, even if it is not particularly difficult? (But I’ll concede that accounting is far from sexy.) Fact is, accounting is the language of business. How many on this forum know how to read a balance sheet and calculate manually simple values such as a price earning ratio, a working capital or free cash flows (*) ? If they are not able to compare the value they are getting to the price they are paying, it is going to be difficult to be able to beat the markets. if a random investor buys Tesla because he loves the company and he thinks it has great prospects, sorry but a deception may occur.

(*) I have been talking several times about accounting lately. If you want a very good and pragmatic introduction to accounting, I strongly advice to start with the first chapters of Pat Dorsey’s „5 rules for successful stock investing“ (warning : the remaining of the book, although exact, is not of great help in my point of view. But the accounting lessons are great!). From there you can move then to more specialized books, or go as well re-read Graham’s Intelligent Investor or Security Analysis to put your newly acquired knowledge into practice

Furthermore, I suspect that active investing is very far from the fanciness and glamour that most people imagine. In reality it is more reading and compiling hundreds and hundreds of financial reports and proxy statements, which I suspect is not exactly the definition of a fun time in most people minds. I personally don’t think that the tools needed for investing are really sophisticated. Rather, I suspect that most people enjoy doing funnier stuffs with their lives!

Therefore, I think that most retail investors :

- Go indexing

- Or often even worse (as indicated in my post on active funds) hire fund mangers to handle their money.

- Now let’s discuss professional investors/managers : it is true that not a lot of professional managers beat consistently the market. However, I will make the following bold statements (feel free to discuss!)

-

Most of them don’t even try to beat the market. There is a risk nobody talks about when thinking about financial managers, but a real risk nonetheless : career risk! The main incentive of money manager are : 1. not get fired. 2. Not lose clients and thus assets under management. Therefore, lagging the benchmark is a real risk for most managers often measured with short term pressure (their performance is measured quarterly, monthly…) I don’t think they are really too eager to go too far from their benchmark. Often, they over-diversify, which results in their best ideas being absolutely diluted by the other stocks they own.

-

When they really try to beat the market using sound principles, they usually succeed (Now you can open the fire against me

) For instance, in a brilliant article dating from 1983 called “The Super Investors of Graham-And-Doddsville” (**), Warren Buffett discuss the EMH and compare it with the performance of 9 real investors, who all had fantastic investing results over the previous 20-ish years. The fact that they all used the same governing principles contradict the survivorship bias and the EMH. Furthermore, the investors in the article continued afterward to have stellar results for a long time until they either die or retire.

) For instance, in a brilliant article dating from 1983 called “The Super Investors of Graham-And-Doddsville” (**), Warren Buffett discuss the EMH and compare it with the performance of 9 real investors, who all had fantastic investing results over the previous 20-ish years. The fact that they all used the same governing principles contradict the survivorship bias and the EMH. Furthermore, the investors in the article continued afterward to have stellar results for a long time until they either die or retire.

(**) I’ve been quoting this article several times as well. I should definitely create a topic with the content of the article! It is really thought-provoking.

Ok, i’ve tried to wrap all of my thoughts about the efficient market hypothesis. I fully expect that some of you won’t agree, but I also expect that through discussion we will manage to sort errors from real points…

just another image i found in the MMM forums:

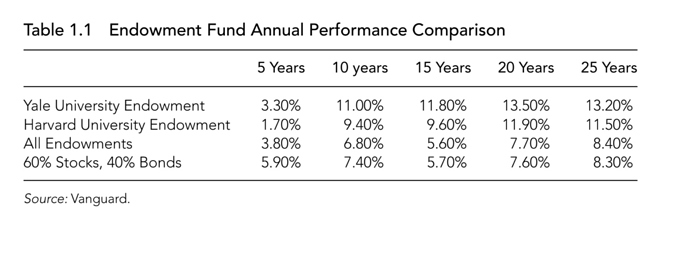

Ben Carlson makes a point in his book “A wealth of common sense”, that even institutional investors free from potential conflict of interest and short-termism, like managers of American universities endowment funds fail to beat the market (with exception of Yale and Harvard):

And even them are aware of this fact. David Swensen, manager of Yale University endowment fund, best institutional investor and one of the greatest investors in general, wrote something like that:

"The most important distinction in the investment world does not separate individuals and institutions; the most important distinction divides those investors that have the ability to make high-quality active management decisions from those investors without active management expertise. Few institutions and even fewer individuals exhibit the ability and commit the resources to produce risk-adjusted excess returns.

The correct strategies for investors with active management expertise fall on the opposite end of the spectrum from the appropriate approaches for investors without active management abilities. Aside from the obvious fact that skilled active managers face the opportunity to generate market-beating returns in traditional asset classes of domestic and foreign equity, skilled active managers enjoy the more important opportunity to create lower-risk, higher returning portfolios with the alternative asset classes, and private equity. Only those investors with active management ability sensibly pursue market-beating strategies in traditional asset classes and portfolio allocation to nontraditional asset classes.

No middle ground exists. Low-cost passive strategies suit the overwhelming number of individual and institutional investors without the time, resources, and ability to make high-quality decisions."

And this writes a guy, who has consistently beaten the market for nearly three decades. Apparently, even best of the best know that it’s enormously difficult for professionals with resources (money, knowledge, analysts, etc.) to beat the market, and that it’s nearly impossible for individual investors.

PS. And even Yale is loosing with S&P500 on a longer time horizon.

Berkshire is 5th biggest position in VT ETF. If you go passive market-cap weight, you actually own nice portion of Buffet’s returns precisely because Berkshire is so huge. If I calculate things properly it’s:

84’713’371 (Berkshire shares market value in VT) / 41’500’000’000 (median market cap of VT) * 100% = 0.2%.

I’m thinking about over-weighting it a bit, though. EM+small-cap+Buffet in my opinion is a good idea to tilt.